To assess competition, he grew the two species together in glass culture dishes.His results:

Does this indicate competition is occurring?

What about a control?

Results from other pairs of species.

| Dept of Biology, Lewis and Clark College | Dr Kenneth Clifton

|

|

Biology

141 Lecture Outline

|

Lecture 17: Species interactions continued: Competition

Species interactions: an introduction to competition.

Recall our definition of a species: a group of individuals capable of successfully exchanging genes with one another.

Kinds of interactions possible between two species (first 3 are most common and most important from evolutionary perspective):

Predation/parasitism/herbivory (+/-): one species benefits, the other is harmed because one species feeds on another (e.g. an insect species feeds on a plant's seeds)

Competition (-/-): both species are harmed by one another's presence, because they each need a resource that is scarce (e.g. two plant species might compete for light).

Mutualisms (+/+): both species benefit from their interaction (e.g. a plant and its pollinator).

Neutral (o/o): two species have no effect on one another.

Commensalism (+/o): one species benefits from its association with another, while the other is unaffected (e.g. an insect living in the bark of a tree).

Amensalism (o/-): one species is harmed but the other is unaffected (e.g. a human tramples a plant on a trail).

Competition between species (interspecific competition).

Definition: two species each need a resource (food, water, shelter, etc.) that is in limited supply, and each suffer a decrease in their survival and/or reproduction as a result.

Distinction between competition in nature and human concept of competition as a game in which there is a prize. In nature, there are no winners, only losers. The "winner" is the species that loses the least.

Relevance to ivy projects: many of you are studying an interaction that you hypothesize represents competition; you should consider using this term as you write about it.

How do we study competition: we have to infer its operation from an observed effect (we rarely see organisms fight over resources).

Experimental studies of interspecific competition.

Gause's work: another study of protozoans (Paramecium caudatum and P. aurelia).To assess competition, he grew the two species together in glass culture dishes.His results:

Does this indicate competition is occurring?

What about a control?

Results from other pairs of species.

Generalizing this concept: The competitive exclusion principle.

When shared resources are in limited supply, complete competitors cannot coexist.

Think of this in terms of niche theory

The competitive exclusion principle restated: no two species can occupy the same niche for long; the less successful species will go extinct.

Given that we understand that organisms often compete for resources, how do we explain coexistence:

Niche partitioning (MacArthur's Warblers)

Keystone predation (Starfish in the intertidal)

Disturbance (models of succession)

Experimental approaches to studying interspecific competition.

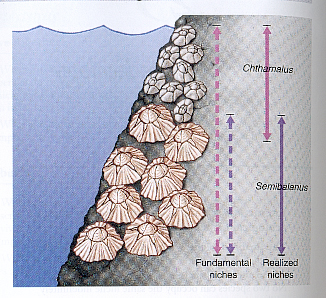

Joseph Connell's study of two barnacle spp. in Scotland: Chthamalus stellatus and Semibalanus balanoides (see section 13.1 in text)

Recall bipartite life history of marine organisms

Initial observations

a. non-overlapping adult distributions in the intertidal zone.

However, larval distribution of Chthamalus overlapped with that of Semibalanus.

Led to hypothesis: over time, the larger Semibalanus outcompeted the smaller Chthamalus.

Test of hypothesis: remove Semibalanus from one area, keep Semibalanus intact in another. Compare Chthamalus success in each situation.

Results: Chthamalus survived equally well in their normal zone and in the lower zone, but only when Semibalanus had been removed from that lower zone.

Conclusion: Species coexistence possible by virtue of having different niches.

How do you know what resource is involved in competition?

What can we do when organisms' distributions can't be manipulated?

Use an observational approach.

Remember the benefits and disadvantages of that approach.....

Example: Jared Diamond's study of ground doves in the New Guinea archipelago.

On the largest, most ecologically complex islands (e.g. New Guinea), each species lives in a specific habitat:

a. Chalcophaps indica in coastal scrub

a. Chalcophaps stephani in light forest

c. Chalcophaps rufigula in inland rain forest

Do they have different fundamental niches? Find out by looking at islands that, by chance, lack one of these species.

Where C. rufigula is absent (e.g. Bagabag), C. stephani lives in both light forest and rainforest.

Where C. indica and C. rufigula are both missing (e.g. New Britain), C. stephani occupies all 3 habitats.

A new kind of evidence for competition = Competitive release: the expansion of a species into new habitat when another species is absent, indirect evidence of competition (careful about the impact of clines).

Some conclusions about competition:

Competition is a mutually negative interaction.

Species that share a need for the same resource will compete if that resource is limited.

Species with identical niches will not be able to coexist, except temporarily.

Species will be able to coexist if enough of their fundamental niche does not overlap with that of their competitor.

Competition between species has the effect of lowering the environment's carrying capacity for each species involved.

Competition can be studied either through an experimental or an observational approach.

Interspecific competition is an important determinant of where species can live and how successful they are