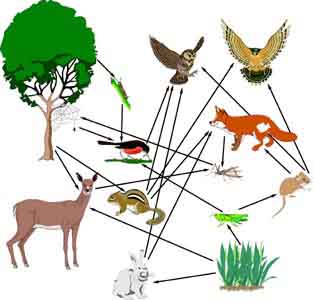

A basic terrestrial food web

Many food webs are quite complicated

A basic marine food web

| Dept of Biology, Lewis and Clark College | Dr Kenneth Clifton |

|

Biology

141 Lecture Outline |

Introduction to community ecology and and interspecific interactions like predation

Moving from intraspecific to interspecific interactions: Communities

Communities are populations of different species that co-occur in time and space.

Typically this includes organisms of diverse biological characteristics (e.g., sedentary / mobile, plants / animals, short-lived / long-lived, etc.)

Defining the boundaries of a community?

Is the notion of "communities" a biologically useful and reasonable approach?

Cohesive units vs. overlapping, independently operating populations

So... what ties communities together?

To answer, examine the "role" that species play within communities

Trophic roles: a revisit to trophic relationships and the concept of food web

A basic terrestrial food web |

Many food webs are quite complicated |

A basic marine food web |

By definition, species interact within a community

Types of interspecific interactions we will study include::

Predation and parasitism: what's the difference?

Competition (interspecific vs intraspecific).

Mutualism

Commensalism

Might these relationships vary through time?

Thinking about succession within a community

What is predation (consumption) and why is it interesting?

How do we categorize consumers?

Categories based on prey taxonomy.

Carnivores

Herbivores

Omnivores

Categories based on effect and type of predation.

True predators kill prey immediately, eat many prey/lifetime.

Grazers consume part of a prey individual, are rarely lethal to the prey.

Parasitoids eventually kill their prey, but slowly; have only one prey ("host")/lifetime.

Parasites consume part of a prey ("host"), are rarely lethal to the prey.

Categories based on breadth of diet.

Generalists eat many different prey types.

Specialists feed on only one or a few prey types.

How do predators and prey manage to coexist (or... why don't predators always drive their prey extinct)?

Evidence from the lab:

In simple systems, predators DO drive their prey extinct; in nature, they rarely do so.

Do predators restrain themselves consciously? NO -- they would lose to natural selection if they did.

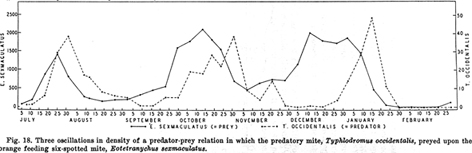

Huffaker (1963) performed a laboratory study using mites as predators and as prey, provides an answer:

Primary producers = oranges in a laboratory tray.

One species of mite was the prey, fed on oranges.

Another species of mite was the predator.

In a very simple labortatory environment, the predators caught all the prey, and then went extinct themselves (see below).

As the environment became more complex, the game of "hide-and-seek" was able to last longer and longer (see below).

Both species of mites showed cyclical populations.

What forces control ("regulate") the abundance of prey populations? Top-down vs. bottom-up control of prey populations.

An example: grass, rabbits, and wolves

With top-down control, an increase in grass will not increase the number of rabbits. But a decrease in wolves would.

With bottom-up control, an increase in grass would increase the number of rabbits, but a decrease in wolves would not.

Predation (top-down control) can keep a prey population's numbers well below their K, and thus permit coexistence between prey species that would otherwise be strong competitors (e.g. the effect of the seastar Pisaster in the intertidal zone). Think about keystone predators.